>August Events / Events in Norfolk and Suffolk / Food and Drink / Tourist Attractions Norfolk and Suffolk September 12, 2017

So you think you know about food?

What is your favourite British food? Fish and chips, of course, perhaps the Sunday roast and the mighty full English breakfast.

Here in Norfolk, we can provide all the ingredients for the top 10 most popular dishes including bangers and mash, cockles, a simple salad or a platter of local cheeses.

And in Aylsham in particular, we are very lucky to still have pastures that give us meat, milk and cheeses of magnificent taste and quality.

We all know that cows eat grass, but did you know that nearly 97 per cent of all natural British pastures have been destroyed?

Sadly, it seems not, as our stand at the Aylsham Show in north Norfolk in August this year discovered.

The theme for the stand was ‘pasture is life’ – an exploration of how our oldest crop, pasture, once provided nearly all of our dietary needs.

As new production techniques are introduced and intensified, the variety of rare breeds of livestock which gave us a range of unique flavours, has been lost and our wildlife, especially flowers and insects, has declined.

In an attempt to show how local producers are trying to correct the balance, we devised a simple quiz.

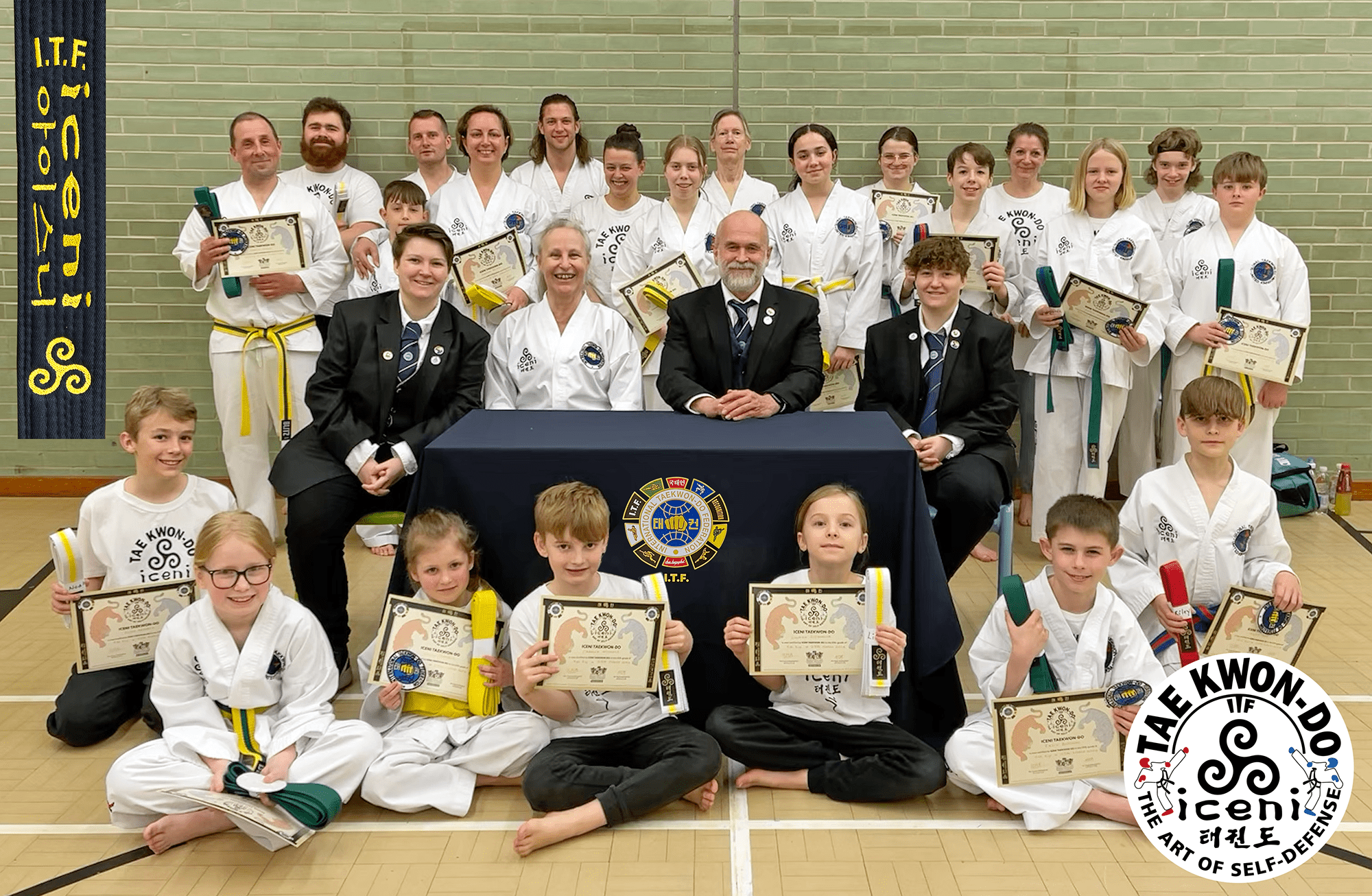

More than 100 people took part in the Norfolk Pastures Family Game which tested people’s knowledge of how much they think they know about local food providers.

The quiz was run from tables in front of three banners outlining the benefits of pasture, and included tests on four of our five senses – sight, taste, smell and touch – and on information banners.

Sindy Littleproud, a retail manager from Dereham, said: “The quiz is very good, especially for children, who all think their food comes from supermarkets. And it was just hard enough to make you think.”

Peter Garrod and Yasmin Burgess, from Ashmanhaugh, said: “It’s a brilliant idea and a lot harder than you think and reminds you just how much you don’t know about food. We’re certainly buying more local now.”

And Carol McKean, a social worker from Sheringham and children Taylor, aged nine and Zoe, 12, said: “It gets people thinking about alternatives. For instance, I didn’t know how many pasture products or cheeses came from Norfolk,” said Carol.

The winner wins a family ticket for the Aylsham Food Festival Big Slow Brunch on Sunday 8 October.

CAPTION: Slow Food Aylsham member Lesley Prekopp tests visitors’ knowledge of food based on their senses.

Moving on to pastures new

Aylsham Agricultural Show theme was based on pastures – pastures are the basis for ‘slow’ dairy.

‘Fast’ dairy, on the other hand, could produce pasteurised homogenised milk from cows in factory farms that never see grass. Moreover, true pastures have been ‘improved’ almost out of existence by intensive modern farming, sacrificing their quality and diversity for quantity.

Pastures have been important to Aylsham for hundreds of years – the town was the centre of the medieval wool trade, through the ports that once did a thriving business along the Norfolk coast trading with Europe.

Our churches, like Aylsham and Cawston, bear witness to that past wealth, based on pastures.

They were an unplanned consequence of forest clearance by Stone Age man more than 5,000 years ago, but became ideal for grazing the newly-domesticated livestock. Right up until the middle of the 20th Century, pastures – with their unique combination of grasses and flowering plants, dependent on the geology and soils – were responsible for this country’s natural (plants and animals) and domesticated (livestock) biodiversity.

All began to change with the Second World War (1939-45) when many permanent pastures were ploughed up to grow crops for the war effort.

After the war, many on the outskirts of towns and cities were lost to housing development and throughout the country many more were lost to ploughing and re-seeding with ryegrass, or treatment with fertilisers and herbicides to encourage greater grass growth at the expense of the flowering (broad leaved) plants.

Today, 97 per cent of our pre-war pastures have disappeared and with them populations of flowering plants, insects, birds and rare breeds of livestock. Our modern society has lost the unique and local taste quality that true pasture-fed livestock can give us through their meat or milk or cheeses, sacrificing it for the bland, cheaper, “identikit” versions in supermarkets all over the country.

Many of the best examples of the remaining pastures are in the care of conservation organisations, such as the Norfolk Wildlife Trust, National Trust or RSPB, or farmers with wider vision – farmers like those at Bure Valley Farm, Aylsham; Hawthorn Farm, Stody; Dole Farm, Hevingham; Bainbridge Park Farm, Blickling; Norton’s Dairy, Frettenham; and many more.

It is ironic that, while natural woodland is rare because of its early clearance for pastures, natural, permanent pastures are now rarer because of their short-term destruction for quantity at the expense of quality.